Highlights

Many tweezers make light work of atom-array assembly

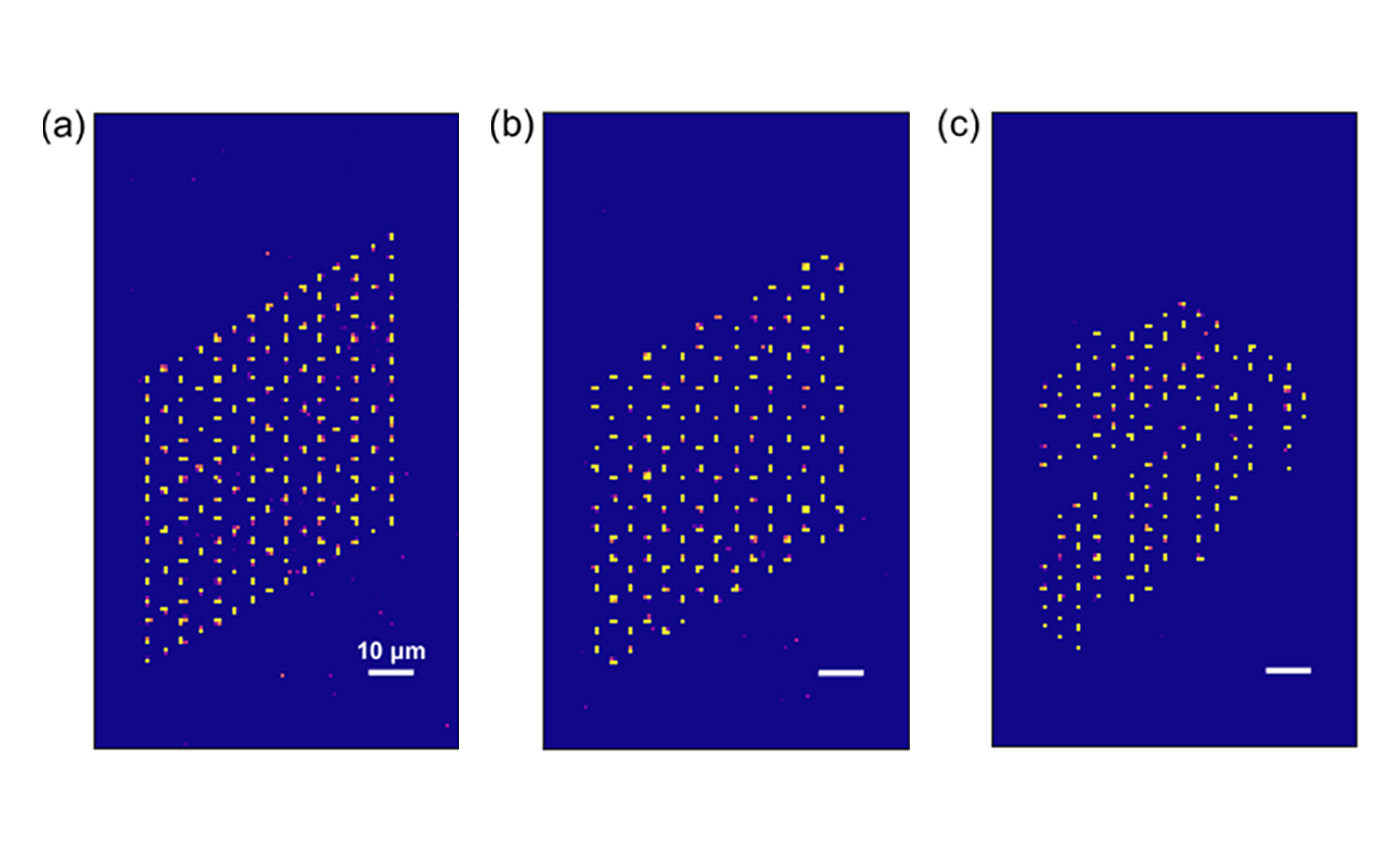

Arrays of neutral atoms are a promising platform for quantum simulation. The group of CQT’s Loh Huanqian can precisely assemble large arrays of singly-trapped rubidium atoms, as shown in these single-shot images of arrays with arbitrary geometries: (from left to right) kagome, honeycomb, and a lion head, which is a national symbol of Singapore.

Arrays of neutral atoms are a promising platform for quantum simulation. The group of CQT’s Loh Huanqian can precisely assemble large arrays of singly-trapped rubidium atoms, as shown in these single-shot images of arrays with arbitrary geometries: (from left to right) kagome, honeycomb, and a lion head, which is a national symbol of Singapore.

The glowing dots in these images are single rubidium atoms, pristinely arranged in arrays about as wide as a human hair. The team of CQT Principal Investigator Loh Huanqian captured these pictures to show how they can assemble atoms into any pattern — even Singapore’s Lion Head symbol — fitting within a 15 by 15 triangular grid. The researchers describe the setup and novel algorithm that makes this possible in a paper published 15 March 2023 in Physical Review Applied. The paper is also spotlighted in the American Physical Society Physics magazine.

Researchers are keen to work with arrays of neutral atoms because, like Lego blocks that can be assembled into prototype buildings, atom arrays can be used to perform powerful quantum simulations of materials. Already scientists use supercomputers to calculate material properties, but the calculations quickly become intractable if you try to simulate more particles. With an atom array, scientists can model materials directly.

The CQT group’s approach allowed them to achieve a state-of-the-art defect-free array size of 225 atoms reliably at room temperature. Perfection in the pattern is important because defects, or missing atoms, in an array have been found to deteriorate the observed signal in quantum simulations.

Huanqian’s co-authors on the paper are research students Tian Weikun, Wee Wen Jun, Qu An, Billy Lim Jun Ming, Prithvi Raj Datla, and Vanessa Koh Pei Wen, all of whom made contributions towards the reported results while working in her CQT laboratory. Huanqian is also a President’s Assistant Professor in the Department of Physics at the National University of Singapore.

Rearranging atoms in parallel

To assemble their atom arrays, the group starts by trapping atoms using laser beams also known as optical tweezers. Trapping single atoms involves an element of chance, so not every tweezer is successfully loaded with an atom. This means that even though the researchers begin with an array of 400 tweezers, they end up with an atom array full of defects. In the next step, they rearrange the atoms in real time to form a smaller, defect-free target array.

This is where the team’s approach diverges from existing approaches. Previous efforts to rearrange atoms have focused on moving the atoms one at a time using a single extra optical tweezer, after calculating the smallest number of moves needed. Atoms do not stay in their traps forever, so minimising the number of moves, and so the time needed for the rearrangement, increases the probability of achieving a defect-free array.

Huanqian and her group members have developed a system that instead speeds up the rearrangement by moving many atoms in parallel with multiple tweezers. In their experiment, up to 15 mobile tweezers can be used to move atoms simultaneously to generate the defect-free array. The maximum number of mobile tweezers involved can be specified by the user.

“Moving the atoms one at a time is like playing the piano with one finger,” says Weikun, who is the first author of the paper. In our protocol, we use more fingers and can play the piano faster, which saves a lot of time. For example, if we had 100 atoms to move, instead of making 100 moves one at a time, we could move ten atoms at a time. This means that the number of moves we make is ten times smaller.”

To make this work, the researchers designed a novel algorithm that calculates what moves to make.

Strategic moves

The algorithm’s input comes from an image of how the atoms are initially loaded. The image is converted to a binary matrix, with values 1 and 0 representing if an atom is successfully trapped in the tweezers or not. The researchers also specify the target array.

The rearrangement strategy consists of two parts. The first is row sorting. In this procedure, atoms in the rows are redistributed among the columns such that each column has the number of atoms required in the target array. The second is a column compression procedure that moves the atoms to their target positions.

To ensure atoms do not collide during moves, which could knock them out of the array, the group specified that the algorithm should always move atoms with the same speed and preserve their order.

After completing the calculation, the algorithm communicates with the hardware. Optical tweezers, acting as mechanical arms, rearrange the atoms row by row, then column by column. The group call their algorithm the parallel sort-and-compression algorithm, which can complete the array assembly faster than a blink of an eye.

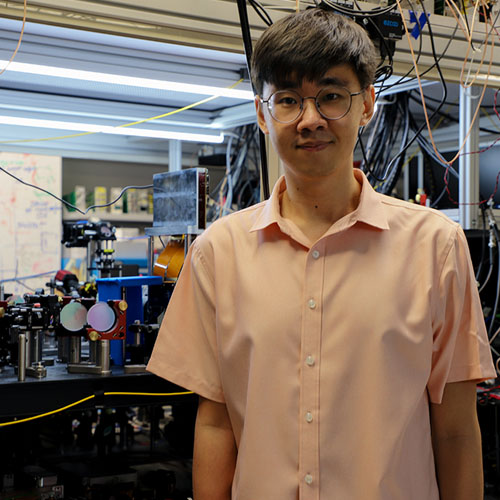

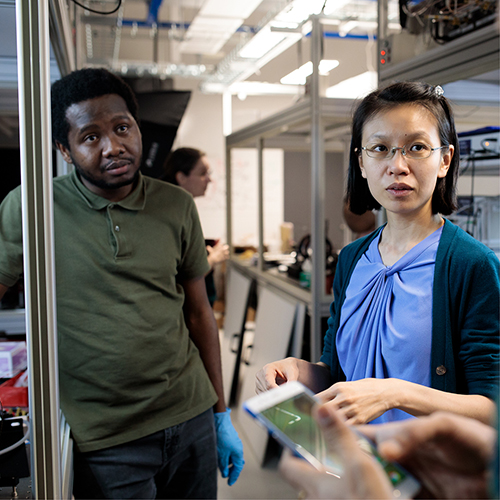

(From left) Group members Weikun, Wen Jun, An and Huanqian with their experimental setup. For the work, Wen Jun has also won the Lijen Industrial Development Medal and Outstanding Undergraduate Research Prize given by the University.

(From left) Group members Weikun, Wen Jun, An and Huanqian with their experimental setup. For the work, Wen Jun has also won the Lijen Industrial Development Medal and Outstanding Undergraduate Research Prize given by the University.

“Coding is one of the most difficult parts of the experiment,” says Weikun. “Our algorithm sees the whole picture, designs the entire move set in one go, makes sure that there is no collision and then conducts it.”

The work is partly funded by a grant awarded in 2022 by Singapore’s Quantum Engineering Programme for “A scalable, programmable atom-array platform for quantum simulation of dynamical and material physics”. This programme is supported by the National Research Foundation, Singapore, which also awarded Huanqian a five-year fellowship in 2018.

With their novel algorithm, the group experimentally realised the defect-free 225-atom array with a success probability of 33%, which is among the highest success probabilities reported in the literature for room temperature setups. The team expects their success probability can be improved with quieter and more powerful laser sources.

“We have demonstrated that we can apply our algorithm to arbitrary geometries such as the honeycomb, kagome, and link-kagome, which are interesting for studying different advanced materials like graphene, superconductors or quantum spin liquids,” says Huanqian. “Just to show that we’ve done this in Singapore, we also rearranged the single atoms to form the Lion Head symbol.” The Lion Head symbol was introduced as a national symbol in 1986 and symbolises courage, strength and excellence.

Learn more

Related Stories

| Meet a CQTian: Wee Wen Jun March 16 2023 |

| CQT researchers land on a magic wavelength for scaling atomic arrays November 01 2021 |

| CQT researchers awarded grants under Singapore’s Quantum Engineering Programme April 21 2022 |