Highlights

Retrospective test for quantum computers can build trust

Tech companies are racing to make quantum computers available to customers. A new scheme from researchers in Singapore and Japan could help customers establish trust in what they get if they buy time on such machines – and protect companies from dishonest customers.

Quantum computers have the potential to solve problems that are beyond the reach of even today’s biggest supercomputers, in areas such as drug modelling and optimisation.

“Our approach gives a way to generate a proof that a computation was correct, after it has been completed,” explains Joseph Fitzsimons, a Principal Investigator at Singapore’s Centre for Quantum Technologies and Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Fitzsimons carried out the work with colleague Michal Hajdusek and collaborator Tomoyuki Morimae, who is at Kyoto University in Japan. Their proposals are published 22 January in Physical Review Letters.

Quantum computers today are bulky, specialised machines that require careful maintenance, meaning that people are more likely to access machines owned and operated by a third party than to have their own – like a quantum version of a cloud service.

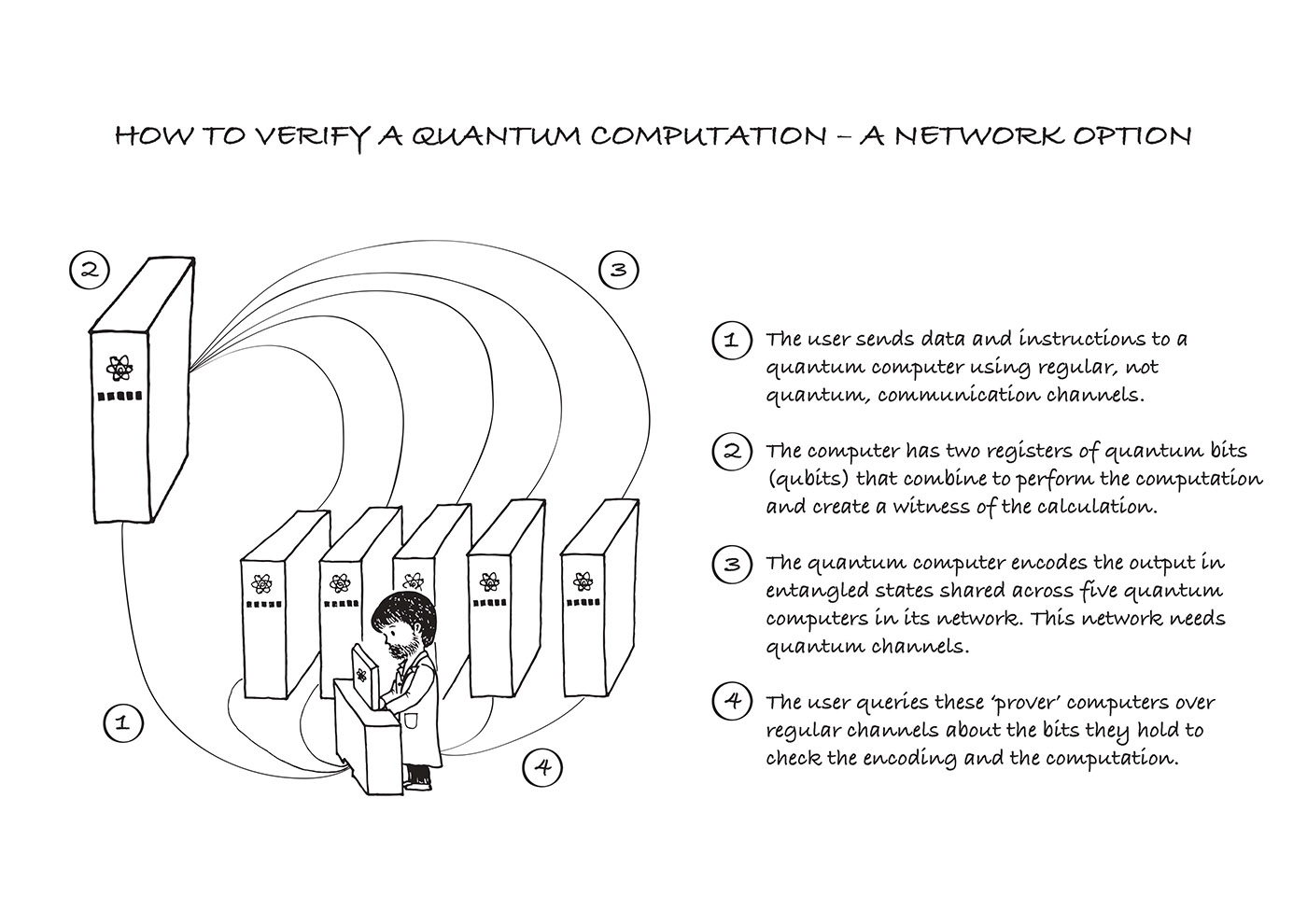

This cartoon illustrates how a quantum computation performed over the cloud could be verified after completion with the help of a network of quantum computers. CQT scientists and their collaborators have published in Physical Review Letters a proposal for such a scheme. Image credit: Liu Jia & Aki Honda / CQT, NUS

This cartoon illustrates how a quantum computation performed over the cloud could be verified after completion with the help of a network of quantum computers. CQT scientists and their collaborators have published in Physical Review Letters a proposal for such a scheme. Image credit: Liu Jia & Aki Honda / CQT, NUS

Customers sending off data and programmes to a quantum computer will want to check that their instructions have been carried out as they intended. This problem of verification has been tackled before, but previous solutions required the customer to interact with the quantum computer while it was running the computation.

That kind of back-and-forth communication isn’t necessary in the new scheme. “If you receive a result that look fishy, you can choose to verify the result, essentially retrospectively,” says Fitzsimons. Verification guards against a quantum computer that does not perform correctly because of an accidental fault or even malicious tampering.

The improvement comes from how the calculation is checked. “The approach is completely different. We try to produce a state which can be used as a witness to the correctness of the computation. The previous approaches had some kind of trap built into the computation that gets checked as you go along,” explains Joseph.

The witness state registers each step of the computation. This means it must have as many bits as the computation has steps. For example, if a computation has 1000 steps, on 100 qubits, the witness would need to be 1100 qubits long.

The research team present two post-hoc verification schemes, based on different ways of testing the witness state. The first requires the customer to be able to send and measure quantum bits. In practice, this means they would need some specialized hardware and a line for sending these qubits to the owner of the quantum computer. The customer then measures the witness directly.

In the second scheme, the customer can be without any quantum tools – communication over the regular internet would do – but the quantum computer doing the calculation must be networked with five other quantum computers that help to check the witness state, playing a role as provers.

“It will be difficult to do an experiment to demonstrate post-hoc verification, but maybe not impossible”, says Joseph. A challenge is the size of the quantum computers available today – the biggest are around 50 qubits. Another is that the networked setups required for the prover schemes don’t exist – at least not yet.

The researchers wrap up their paper by pointing out an interesting advantage of the post-hoc verification scheme: It’s not only the customer who could check that a computation was carried out correctly. The scheme allows ‘public verifiability’. The witness could be checked by a trusted third party, such as a court. This could protect the company if, say, a customer claimed the computation was not done correctly to avoid paying for the service.

Learn more

Related Stories

| Why you might trust a quantum computer with secrets - even over the internet July 12 2017 |

| Scheme checks answers to quantum computation October 01 2013 |